Driving the newsThe MGNREGA – a flagship UPA-era program that guaranteed 100 days of wage employment to rural households – has been replaced by the Viksit Bharat–Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) or VB-G RAM G Act.Union minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan framed it as a bold leap forward: “This is a far better scheme that will completely transform villages.”Critics, led by Congress leader Sonia Gandhi, allege it’s a stealth demolition of rights-based welfare: “The very structure of MGNREGA… has been annihilated.”But beyond the political heat, the quiet engine driving this reform is economic evolution. India’s welfare state – and rural labour market – has changed dramatically since 2005. The logic behind G RAM G isn’t just political; it’s economic.

Why it matters

MGNREGA was designed as a safety valve. Its purpose was simple: if private work dried up, the state would step in and guarantee wages. It was meant to stabilise consumption in bad years and give the rural poor bargaining power in the labour market. On those terms, it succeeded.But it is no longer the India of the mid-2000s.

- In 2005: Rural safety nets were thin, bank accounts rare, and the idea of digital transfers futuristic.

- In 2025: Over 80 crore people get free food grain for the next five years. DBT has matured.

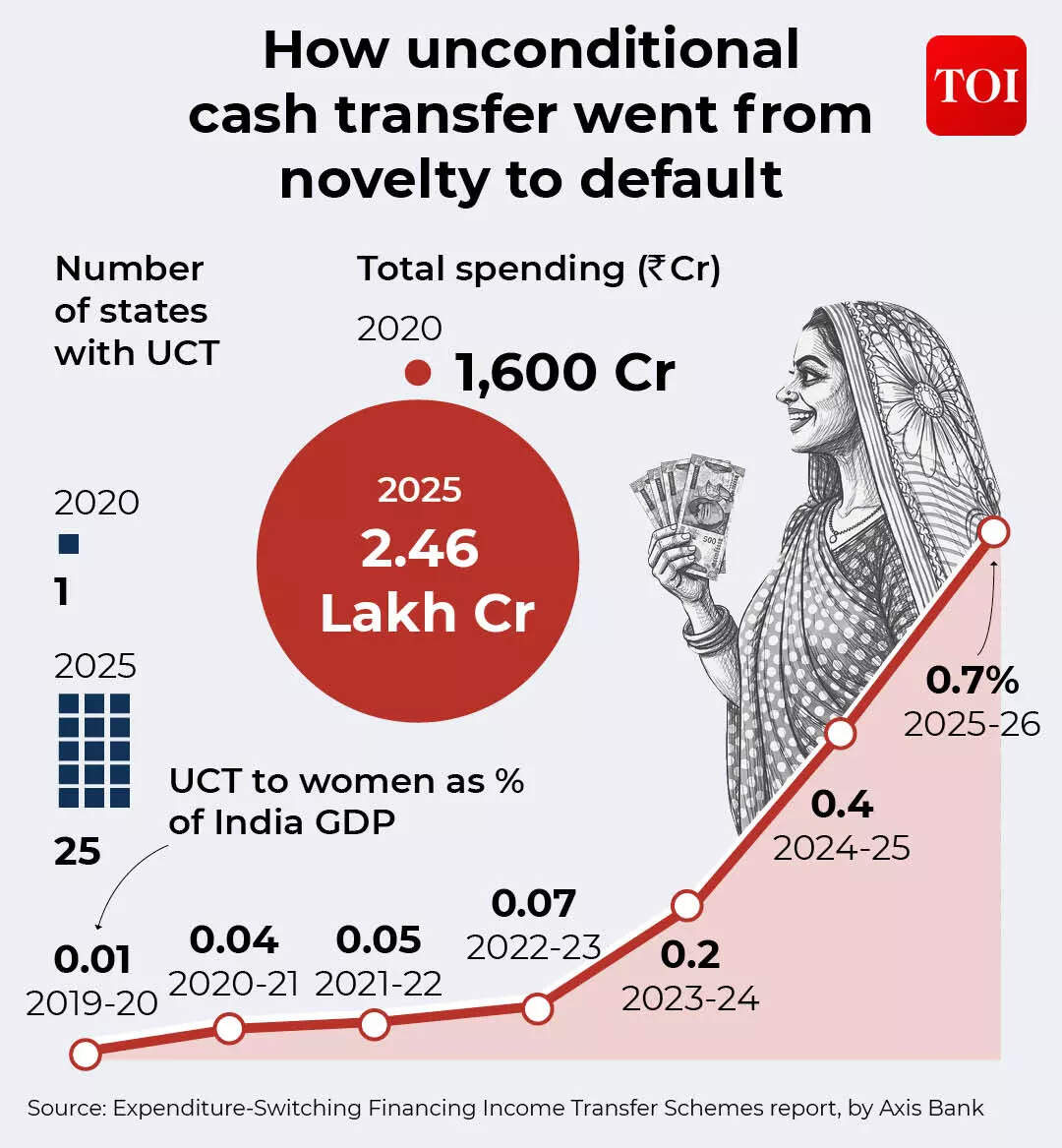

- States are pumping Rs2.46 lakh crore annually into direct cash transfers to women.

MGNREGA, while historic in its impact, was built for an older economy. G RAM G is designed for a digitally connected, subsidy-rich, rural India where the challenge isn’t only poverty relief – it’s productivity, asset creation, and aligning with farm realities.

The big picture: Not a tweak, but a rethink

At a farmer rally in Rajasthan, Chouhan underlined the new mission:“We have not reduced it but increased it… Labourers will get wages and villages will see comprehensive development. Roads, drains, schools, everything can be built.”That shift – from emergency wage distribution to rural asset generation – reflects a deeper economic change.

What they’re saying

Sonia Gandhi calls G RAM G a “collective moral failure,” warning of job loss and loss of dignity: “The removal of the Mahatma’s name was only the tip of the iceberg.”The BJP’s Amit Malviya hit back: “Her arguments rest on mischaracterisations, selective memory, and outright falsehoods.”The divide is ideological – but also generational, rooted in two welfare philosophies: permanent subsidy vs productivity-driven support.Rahul Gandhi called it an ‘insult to the ideals of Mahatma Gandhi‘ and said the law bulldozes “both MGNREGA and democracy.”

Between the lines: The real economic logic of G RAM G

1. The safety net is now a floor, not a fallbackMGNREGA was built to prevent rural starvation and mass migration during crop failures and lean seasons. That logic worked in 2005.But today:

- PMGKAY offers free food grain to 80 crore people until 2029.

- NFSA guarantees subsidised food to two-thirds of India.

- DBT infrastructure reaches 45 crore beneficiaries.

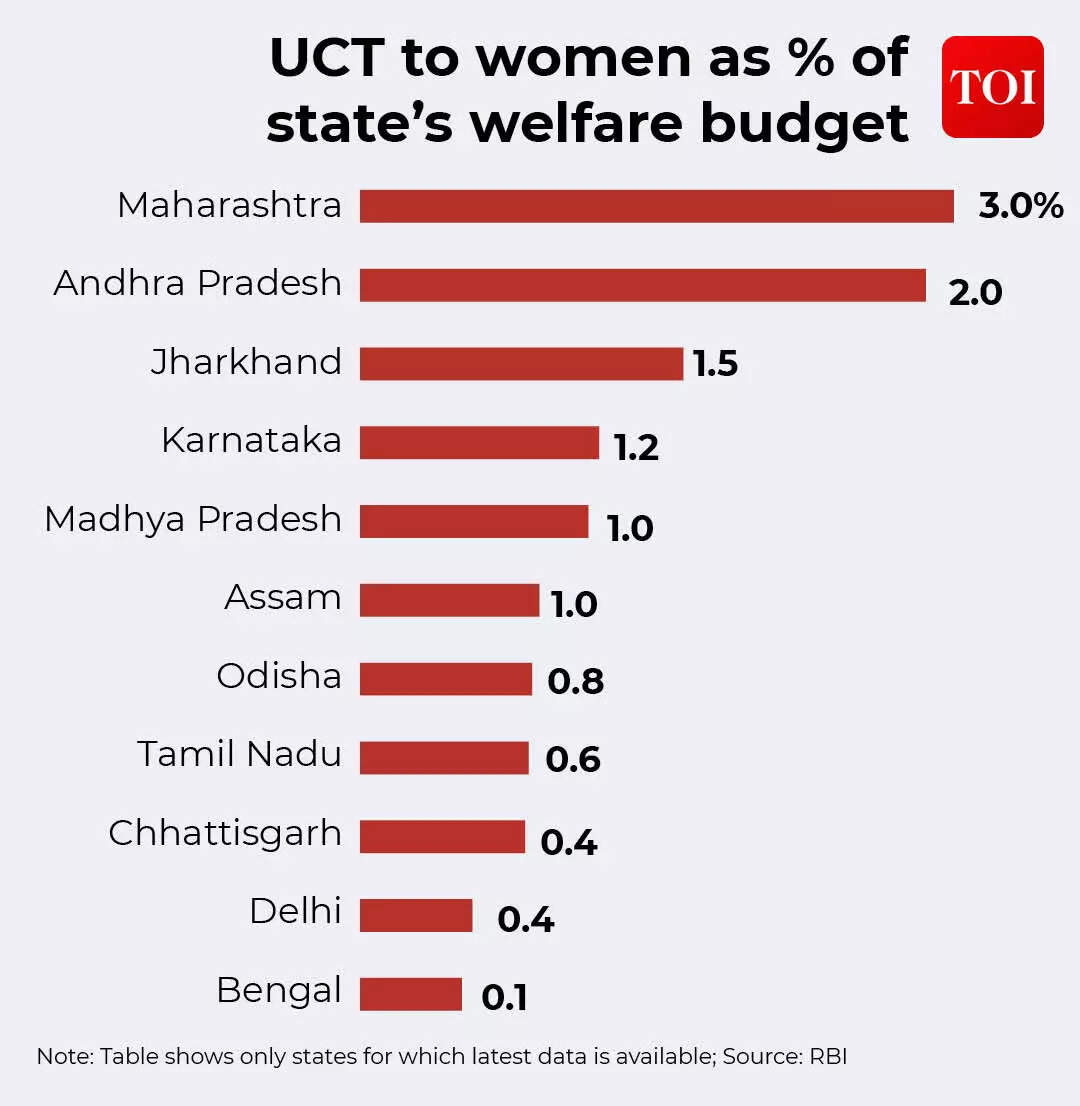

Implication: With calories protected, the role of employment guarantee schemes can shift from consumption smoothing to income generation through durable assets.In Chouhan’s words, “If needed, farm roads can also be constructed… everything can be built.”2. States are already flooding households with cash – so duplication is inefficient.From 1 state in 2020 to 15 states in 2025, unconditional cash transfers (UCTs) to women are now a Rs 2.46 lakh crore juggernaut.

- Madhya Pradesh: Ladli Behna Scheme – Rs 1,000–Rs1,500/month.

Karnataka : Gruh Lakshmi – Rs 2,000/month.- Telangana: Mahalakshmi – Rs 2,500 + LPG subsidy + free bus rides.

.

Why this matters: In villages where households already get regular cash + free food, demand for physical labour schemes changes.Women – the primary MGNREGA participants – are less likely to show up for work at Rs 220/day when cash arrives in their bank.

.

G RAM G acknowledges this by focusing on village development outcomes, not just labour targets.

.

3. G RAM G fixes a paradox MGNREGA helped create: Labour shortages during harvestOne of the least discussed but most consequential changes is also one of the most controversial: The ability of states to suspend works for up to 60 days during peak sowing and harvesting seasons.Under MGNREGA, this was effectively taboo. Work was meant to be available year-round, on demand. But over time, farmers across states complained that the programme had become a rival employer. During peak agricultural seasons, when labour was needed most, workers often chose guaranteed public works instead. Wages rose. Harvests were delayed. Small farmers paid the price.The new law openly acknowledges this tension. By allowing a notified pause during peak seasons, it treats the employment guarantee not just as welfare, but as a labour-market instrument that must coexist with agriculture rather than crowd it out.States can pause work for 60 days to prevent a labour squeeze during critical farming periods.This reflects labour market realism, not policy retreat. In today’s India.

- Farm productivity is vital.

- Labour availability during key agri windows is essential.

G RAM G helps re-sync the rural workforce with agri cycles, rather than cannibalising farm labour.“They (MGNREGA) are trying to scare labourers… but we have increased the days to 125,” said Chouhan.4. India needs to move from “supporting poverty” to “building capacity”India’s economy is set to cross $4 trillion soon, but per capita income remains modest – around $2,800/year.That creates a challenge: How do we support vulnerable households without freezing them in place?“The real nature of the Modi government’s intentions can be understood from its decade-long track record of throttling MGNREGA,” Sonia Gandhi wrote in an article in a national daily.But G RAM G’s supporters argue the opposite: the scheme is not abandoning rights but upgrading them

- From income support to income generation

- From person-days to water tanks, roads, climate resilience

- From centralised bureaucratic design to village-level planning

By raising guaranteed work to 125 days and channeling it into productive, measurable outputs, G RAM G aims to raise village capability – not just survival.

What next: Execution is the litmus test

Even the most elegant economic theory fails if delivery falters. G RAM G’s success hinges on four critical design principles:1. Avoid stealth caps: Centre determines normative funding per state – but must ensure that does not limit the legal guarantee.2. Use the 60-day pause wisely: It should match local agri calendars, not become a loophole to under-provide work.3. Biometrics must include – not exclude: With tech-driven tracking, grievance redress and offline options must remain strong.4. Measure outcomes, not just inputs: Focus must shift from how many people worked to what got built, how it’s used, and what productivity gains it generates.

Zoom out: The economics of co-ownership

The 60:40 Centre-State cost sharing is controversial but crucial. It ends the previous model where states authorised spending and the Centre paid the bill.Now:

- States must co-own work quality.

- Panchayats get more voice in planning.

- Centre retains unemployment allowance provision – if work isn’t provided in 15 days.

Chouhan assured at the rally, “Funds won’t be swindled. Wages will be paid with interest if delayed.”It’s a governance pivot: from passive disbursement to performance-driven delivery.

The bottom line:

VB-G RAM G is not just a renamed MGNREGA. It’s a fundamentally new compact between India’s rural poor, its states, and its economy.In a welfare-rich, DBT-driven, digitally connected India:

- Safety nets must become springboards.

- Cash cannot replace infrastructure.

- Relief must evolve into resilience.

G RAM G, with all its caveats and criticism, tries to answer a simple but vital question: What should rural employment guarantee look like – in a $4T India where the real challenge is not food or cash, but opportunity?